Elskede, det er jeg

som har tatt

plommene

som stod i

kjøleskapet . . .

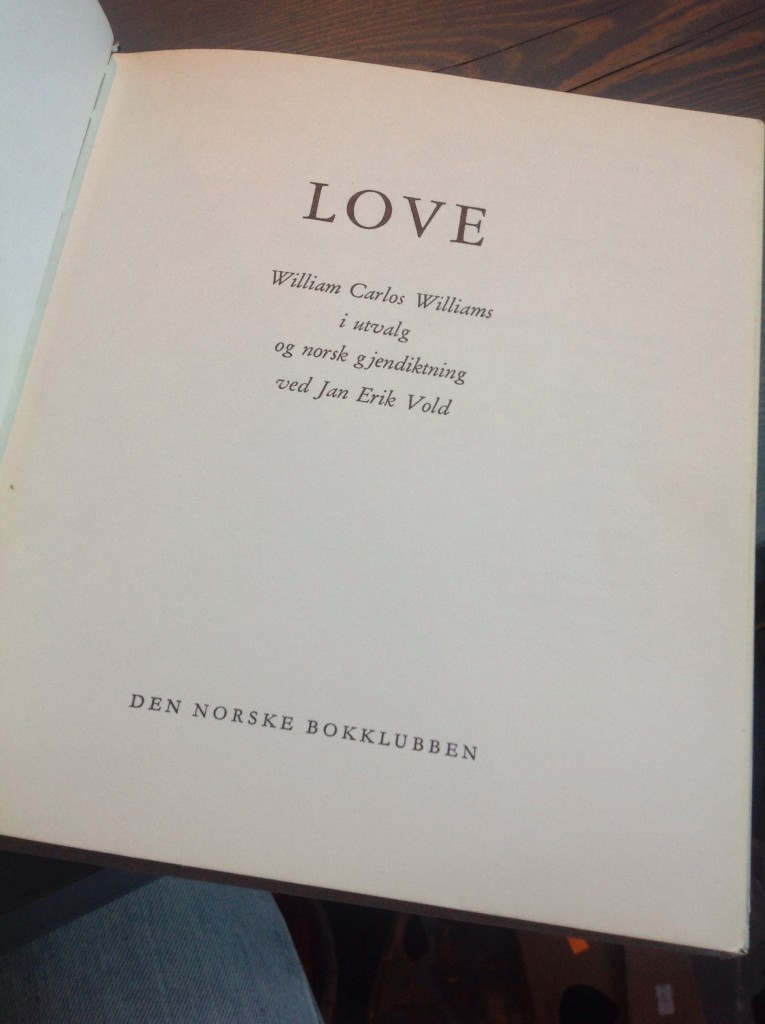

That’s how the translation of William Carlos Williams’s “This is just to say” begins in the collection I found at a flea market in Grünerløkka today. I should be clear, though: it’s not a translation of Williams, but rather a gjendiktning, which literally translates to “re-poeming,” or reinvention (surely drawing on my old favorite, poiesis as invention). So, I sat down in the sunlight outside of my favorite Oslo microbrewery (so far), Grünerløkka Bryggehus, and read a few of Williams’s more well-known poems to see what the translator did with them. (While I read, I enjoyed a very, very tasty pale ale brewed with pors leaves—I’d never heard of pors, and discovered it’s an herbal shrub that grows in Norway and other northern climes. Its Linnaean name is Myrcia gale and its common name is bog-myrtle or sweetgale. Neither have I seen before. But I’ll be, it makes for a lovely beer.) I found my way next to Hendrix Ibsen, a cleverly named beer/coffee/vinyl cafe I’ve taken to, and am a’gonna whip up a tiny spell of poetry chatter.

So. The translator, poet Jan Erik Vold, seems to be after the sense of Williams’s poems, done up in Norwegian rags, rather than WCW’s madly plainspoken specific (American) words—or, maybe, things (no ideas but in them, after all). This reinvention is evident in Vold’s rendition of “This is just to say,” among Williams’s most well-recognized and most anthologized poems. “Elskede, det er jeg” means “My love, it is I,” so that the poem’s title, like the original, is also its first line, but now without the self-referentiality (“this” is just to say). So, it reads thusly:

My love, it is I

who has taken

the plums

that were in

the refrigerator . . .

And so on. It doesn’t have the same spirit, I think. Williams’s confession in the original sneaks up on you; you don’t know he stole those sweet, cold plums from his beloved until a few lines in, when he reveals his assumption that she was probably saving them. Vold, on the other hand, comes right out with it from the start. It was me, baby! From glancing through his afterword, though, I think Vold is nevertheless a good reader of Williams; he knows what he’s doing, and he’s thinking about it (and he’s quite a well-respected figure in Norwegian poetry, apparently). Moreover, he certainly he has the native, nuanced, stylistic sense of quotidian Norwegian usage that I lack. For example, in the afterword, Vold says “Noen teoretiker var ikke Williams, ingen systembygger—no ideas but in things er hans favoritt-maksime: det fins ingen idéer annet enn i tingene—(ikke idéer men ting! skal det på norsk få lyde i imperativ).” Which says, in my rough translation, “Williams was no theorist, no system builder [systematist?]—no ideas but in things is his favorite maxim: there are no ideas other than in things themselves—(not ideas but things! gives it, in Norwegian, the expression [or sound] of the imperative).” I might quibble with the suggestion that Williams wasn’t a theorist (Spring and All is among the best theories of imagination there is), but one can make one’s arguments. My point is that Vold has thought about Williams. His “ikke idéer men ting!” struck me as a poor translation, missing the crucial preposition “in” (“not ideas but things! is quite another, uh, thing)—but clearly Vold has considered the difference, even if I disagree with his choice in the end. Still he swings right past some fastballs over the heart of the plate. The opening of “Til Elsie” (“To Elsie,” of course), for one, reads like this:

De fineste folk i dette land

går dukken—

fjellbønder fra Kentuckyeller slike fra Jerseys ødslige

trakter i nord . . .

The translation:

The finest people in this land

go under—

mountain farmers from Kentuckyor likewise from Jersey’s desolate

tracts in the north . . .

“The finest people in this land”?! It may have a folksy sense about it that’s in some way appropriate to what Williams is after (or he’s trying to be ironic), but “the pure products of America” constitute such a remarkably specific idea, especially with the Kentucky mountain folk and Jersey scrappers biting at its heels. The real irony is that it’s an idea very much knotted up in America’s sharp severance with the far older, deep-rooted European culture from which America sprung. So maybe it makes sense that a European translator wouldn’t immediately or naturally inhabit that meaning. It’s possible that Vold had simply misread the poem, that he somehow missed what “the pure products” connote, that it’s a historical quality Williams is talking about, not a judgment of the “fineness” of the products, as in “pure” honey or a “pure” tone. Swiiiiing and a miss. But the phrase “går dukken” means “go under,” literally—to be submerged. Or, as the bartender at Hendrix Ibsen helped me understand, it can also mean, informally, “go to hell,” as in “that plan went to hell.” Which is a striking choice, since there are alternatives, like blir gale, that would more directly signify “go crazy.” Here, however, I like Vold’s reinvention quite a bit.

But this is fun. What a sweet little surprise at the flea market (which I likewise had only stumbled upon). The collection also includes a resetting of “Asphodel, that greeny flower,” which of course insists that

Vel kan det være

ugreitt å gripe hva nytt diktene bringer

men folk dør hver dag, ulykkelig

av mangel på hva

som der står.

Or,

It may well be

confusing to grasp what news poems bring

but people die every day, unhappily

for lack of what

stands there.

Did Williams mean to imply that poems bring the news, whether readers grasp it or not, as Vold’s resetting suggests? Or does Williams’s original phrase, “It is difficult to get the news from poems,” mean just what it says: that it’s difficult, whether the news is there or not? Williams’s locution is a sort of response to Pound’s notion of poetry as “news that stays news”—a handy turn of phrase, but a less exact idea, perhaps, than Williams’s. Indeed, there’s a lot of shitty poetry that certainly isn’t news anymore, though still I’d call it poetry. Not all water is a glacial spring, after all. But even sewage is still water.

Maybe there’s a new Roving Scholar workshop in here somewhere, for the right group of students.

Kevin

Pors sorta sounds a lot like Beechwood, right?