Into June now, the final month of my opphold—residence—in Norway. I’ve just returned to Oslo from my final school visit of the year, at Flora Vidaregåande Skule1 in Florø, Norway’s westernmost town, in Sogn og Fjordane, which represents the nineteenth of Norway’s nineteen fylker (counties) that I’ve visited as part of the work for this most magical of years. Some up-summing numbers are in order, I think:

I visited:

61 schools (including

11 schools on islands) and

3 prisons in

19 Norwegian counties plus

1 Norwegian territory. Over

135 days of teaching, I gave

315 presentations to approximately

8582 students and approximately

598 teachers. I spent

50 days above the Arctic Circle, reached a northernmost point of

78° latitude, and landed at

11 Arctic airports. I took

32 flights,

3 boat trips (1 on a ferry and 2 on the Hurtigrute), and

2 overnight trains in the course of my official travels.

Here at the edge of June, I grasp wildly among the sea of experiences in vain attempt to capture something that will do justice. I feel a little like Roy Batty at the end of Blade Runner: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Hurricane force winds off the shoulder of Magerøy. I watched Auroras glitter in the twilight near Vesterålen. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears . . . in . . . rain.” Or, with a touch less melodrama, I feel like Inigo Montoya: “Let me explain. No, there is too much; let me sum up.” No matter which way you slice it, a year as a Roving Scholar is characterized by its too-muchness; it stands in excess of description. This is no surprise, of course. But the challenge communicating the experience will doubtless be exhausting as I re-enter an American pattern I once knew—the fair Pacific Northwest, among other mountains, other sounds. That will come soon enough. And nothing for it but to go in.

Meanwhile, in my braincase swirls an infusion of all the senses, reactions, perceptions, reflections, memories, &c. And throughout, there’s the special sense of having sunk partly into this furet, værbitt land, glacier-carved and wind-beaten. For one thing, when I arrived at the beginning of the year, I hesitated to say “I speak Norwegian” without some qualification. I had a good background in the language, to be sure. I could carry on in very basic conversations, though with a lot of guesswork and a limited capability to participate fluidly, especially among stronger dialects or in groups of friends. I took every chance I could to practice, even though it was at times exhausting to keep up. Today, though, I can say I speak Norwegian. I make lots of (sometimes really funny) mistakes. I have a long way to go (and I do long for a second, a third, hell, a twelfth year), but I know I’ve stepped fully into the woods—I feel like I see both the forest and the trees. That’s a really good feeling. And in a way, the language has helped me form relationships that have deepened my sense of the place, and have helped me move, so to speak, partly under the skin (or, maybe better, it’s helped Norway move partly under my skin). The peculiar magic of the place is its fantastic cocktail of people and landscape. They’re knitted into each other. It will not be easy to leave. I’ll soon have crawl out of the land itself, but I sure as the north wind won’t be able to crawl out from under its spell.

Still, much of the wonder of a year like this is predicated on the work itself. A Roving Scholar lives in the best of most worlds, practicing the most rewarding parts and avoiding the tiresome dimensions of teaching. Teachers throughout the country would ask me routinely, “Isn’t it exhausting to travel all the time, live out of a suitcase, constantly meet new people, give the same lecture after the same lecture, the same workshop after the same workshop, move, move, move?” Yes. The answer is yes, it absolutely can be. However (I would say), when the school day is finished, so am I. I have no essays to grade, no homework to track down, very little administrative paperwork, no after-school responsibilities. When the school day is finished, I ask a teacher about the best woods to wander or ski trail to gå, the best local mountain to hike or island to visit. On top of that, a Rover is, in one sense, an automatic freshness, something new for the students, simply by virtue of the fact that I’m not their usual teacher, whom they see every day. Even the finest teachers cannot thrill their students on the daily; they become normal, customary, comfortable. But a Rover rolls in and is new. That’s a luxury. For my part, that performative moment generates a lot of energy.

I don’t want to give the wrong impression, however; the work was highly demanding. At our final meeting, we three Rovers joked about how you could never do this for more than a year. I was nervous before every single workshop. I was beat by every weekend. I packed and unpacked my backpack like it was my job (but then, it was my job!). And I missed one of the very best parts of teaching: enduring relationships with students and colleagues. The work of a teacher—working with students that you learn to know and in contexts you help to shape over a long run—is especially rewarding, and a year as a Rover, without those evolving relationships, is a palpable reminder of that.

It is, in the end, work that delineates so much of much of culture, so many dimensions of a given society. One of the reasons I became interested in applying for a Roving Scholarship was to try and see first-hand how a nation I had already loved went about shaping its social values, among them a strong sense of community, a sort of dugnad culture, and a thoroughgoing commitment to social welfare. As I’ve written elsewhere, Norway’s social celebration of labor is evident nationwide, but it’s also visible in the schools. Unlike American high schools, the Norwegian videregående education system is divided into several “tracks” or lines of study. Students who choose to attend high school select one of two directions: studiespesialisering or yrkesfag programs. Studiespesialisering (literally “study specialization”) is effectively the standard, generalized “academic” line of study, preparing students for post-secondary education. Students who choose yrkesfag, “vocational disciplines,” select one of many lines of vocational training, such as bygg og anlegg (building and construction), teknisk og industriell produksjon (technical and industrial production), restaurant- og matfag (restaurant and food service), or musikk, dans, og drama (music, dance, and drama), among others. Yrkesfag programs require basic general education (e.g., in history, language, social studies, etc.), but to a significantly lesser degree than studiespes. This division between academic and vocational lines is, to me, the greatest difference between American and Norwegian education, though American students finish high school one year earlier than Norwegians. Norwegian education, to my mind, is much more immediately practical: the yrkesfag lines that are available are, generally speaking, suited to what the Norwegian labor market demands. They change over the years as the labor market changes, and in a nation with a near guarantee of employment, it matters. One of my instinctive reactions is to read the Norwegian model as much more practical and efficient than the American model. There’s (ideally) not a lot of “heat loss,” so to speak, in the Norwegian education system; there’s less emphasis on individual desires, and more on the usefulness of the education system (and the educated citizens it produces) to the whole society. Students who graduate Norwegian high school are, in theory, employable and useful, both in filling society’s various roles and in contributing back (by way of, say, taxes) to the economic livelihood of the nation. In the US, the conventional wisdom of the system is “become what you want to be!” which carries with it some inherent risk of losing people (and potential workers) to the wayside, of creating less useful humans who don’t have a sense of responsibility to the system (and to all the “others” it contains) baked into their ethos as citizens. We create “citizens,” we say, but I’m not sure we really know what that means anymore, especially given the state of the political debate in the US and, needless to say, the current monstrosity of an election, an international embarrassment, a sham, a shame. An unclear, incoherent vision of “citizenship,” a somewhat false story of our national origin which generates what is, to my mind, a bizarre and misplaced “pride” in being American, combined with a relatively vague dictum to “be yourself,” whatever that means: this isn’t the recipe for a deeply effective national education system or a citizenry developed out of a shared sense of responsibility for each other’s well being, each other’s welfare.

Still, while I love Norway’s education system for what it is, I’m not an outright apologist for it, either. I’m not sure whether one system is better than the other; they’re simply different systems adjusted to the socio-cultural values out of which they emerged and which they are, almost by definition, designed to perpetuate. Americans seem to want free public education—or, at least, they expect it—while they refuse, at the political level (and far too often at the individual level as well), to pay for that system, because of a weird tradition of tax-hatred and a culture of consumerist self-interest, combined with a widespread distrust of government in general. The source of those problems is a whole other set of essays I’m totally unprepared to write. And yet, for my part, I love the somewhat inefficient value at the heart of American education: find your passion, and then feed it. Care for yourself. I’m suspicious, for lots of reasons, of too much efficiency (in part because I think there are so many dimensions of a human life that cannot be measured and whose “productivity” or “usefulness” or “output” cannot—and should not—be maximized). But if the value of self-care and “find-and-do-your-good-thing” could somehow be knitted into the pattern of a citizenship based on mutual, social welfare instead of knee-jerk individualism, we’d have something pretty special. But we don’t quite live there.

Norwegians, in many ways, live pretty close to that place. In conversations I’ve had in Norway, I’ve observed how deep the ethic of pragmatism runs, but there are wonderful “clefts and cones” that burst up through the map of the sea floor and reveal those immeasurables. Norwegians are aware of the high cost of their social welfare system and the humane values that come with it (their famous mandatory paid parental leave, for example, and their insane amounts of vacation time, with mandatory savings for vacation money!), and they don’t LOVE paying taxes. Of course not. But they seem, on average, to see it as a cost worth paying so that as close to everybody in the system as possible can ha det bra. That value drives both utilitarian and seemingly more humanitarian behaviors. For example, I visited three prisons this year, and in a conversation with one teacher who works in a prison school in Hordaland, I learned that the system is predicated on the notion that the economic contributions to society that a single rehabilitated prisoner will inevitably make when they get out of prison, largely by way of taxes and labor-value, are in total greater than the cost of paying the salary for a teacher’s hours teaching in prison during their entire career. So alongside the humanitarianism in Norway’s famously humane prison system lies a very practical, almost mechanical motivation for that rehabilitative work. I also saw the marriage between utility and humanity in the students I met and the way their lives are organized. (It’s not, I should say, always a happy marriage.) Because of the grouping of yrkesfag students, certain behavior patterns emerge. A bunch of bygg og anlegg boys (and, sadly, it’s usually mostly boys who choose that line) can become a little echo-chamber of typical boneheaded masculinity, the sort of which I’m not especially fond. And yet I had beautiful conversations with some of those boys. In one school in Nordland, I met with a big group of TIP (technical and industrial production) students. After my workshop, several curious guys stuck around to talk. One of them was going to be a plumber. He asked me, “do you know what the best job in the world is?” I said, “a teacher, of course!” He said, “Nope, it’s a plumber!” A plumber is a teacher, too, he reminded me, when they have an apprentice. And think about it, he insisted, you see those pipes under water across the strait there? Yes, I could. Those are for turbine systems for tidal current power generators. The future of energy. And you know what they need to fit and maintain and understand all those pipes? Plumbers. Here was a young person in a very practical education system who had a natural and genuine appreciation for, and moreover, a thoughtful pride in the work he chose to pursue, and for the usefulness of his work to the society of the future. I want to be clear, though: I don’t think that’s the norm in Norway, even though it’s there. You find the same kind of thinking in the US too, if you’re looking for it. But it’s that genus of thinking that builds so many of Norway’s systems.

What draws me to that student’s story is the kind of pride he expressed, one that emerged out of his clearly having thought about the value of his work, the work he had chosen—presumably after some thinking, or because of a family tradition, or what have you. It wasn’t the kind of knee-jerk pride in, say, “being American” that we see all over the states when people at, say, political rallies or country music festivals or large sports events. In another school in Troms, I met with a group of elektrofag students, studying to become electricians. I gave a talk on diversity and stereotypes in the US, in which I try to give a pretty complex version of some of the factors that inform some of the uglier stereotypes of Americans, followed by the realities of our manifold, multiethnic, multicultural, increasingly urban population. I tell students I’m not a cheerleader for the US. I have a healthy criticism of my native country, I say, and I’m not too shy to tell them what frustrates me or what I find compelling about the US. After my talk, a rather engaged student in the very back of the room asked me a question that surprised me, despite its simplicity: “Are you proud to be an American?” he asked. Uff. In a way, it’s an obvious question, but nobody had yet asked it with such clarity. I didn’t quite know how to respond right away. I thought for a while. And finally, I said, “No, no I’m not ‘proud’ to be an American. But I do love being an American,” I said, “and I feel very lucky to have been born into the situation I was, with the opportunities that have been available to me because of being an American of my particular kind and time and place. But I don’t think ‘pride’ has much to do with that. And I’m not proud of the fact that the same access to opportunity that I’ve enjoyed has never been shared by far too much of the population, despite the stories we love to tell ourselves; I’m not proud of many of the things my country has done around the world over the centuries and today, with the brute force of its oversized military; I’m not proud of what the current presidential election reveals about the state of political consciousness in my country; I’m not proud of the gun culture that seems to have swept the nation.” Ultimately, I said, “I’m fascinated by my country. I think it has some of the most beautiful lands and waters and ecosystems in the world; it is full of endlessly diverse, endlessly different people—a manifold of ideas and ethnicities and values; it is full of untold wonders and possibilities. So I love it. But ‘pride’ has nothing to do with it. I cannot say I’m proud. That’s something different, I think.” By almost any measure (other than various “sizes,” such as the size of our economy, the size of the national budget, the size of our military), we are not “number one.” Not in education. Not in voter participation. Not in “democracy.” Not in income equality. Not in the Human Development Index. Not in happiness. Not in freedom (especially, again, considering how many American citizens do not share in the “freedom” we talk so much about). We are, rather, one nation among numerous free-ish nations in the world. We just happen to be a really big one that has had trouble admitting that the world has changed and is constantly changing and the United States of America isn’t any longer so exceptional among developed, democratic nations. And that, dear readers, is OK! That’s a fine thing to be, especially if we can begin to spend a little less energy on chanting vacantly about our greatness and a little more on electing careful, caring, intelligent, sensitive officials, on developing programs and policies and practices that will serve people and nurture a value of mutual support and care and selflessness and curiosity, and craft a culture that we actually can celebrate, even after we really look at it.

William Carlos Williams took up a similar issue in Spring and All in 1923 that I’ve often used in my American Literature workshop this year. Williams begins one of the poems, today called “To Elsie,” by demanding that “The pure products of America / go crazy.” If you can locate a “product” of the United States that is purely American, whose cultural origins are not from elsewhere (and, based on his examples, not American Indian either), that product, that person or people, that cultural form, will exist in a crazed state, “[w]ith no peasant tradition to give [it] character.” With the important exception of American Indians, most Americans have no ethnicity in place, no long ethnic tradition to stand upon in order to imagine what it actually means to be American, what an American citizen does, what values shape the behaviors and systems that an American citizen enacts. Norway, on the other hand, is somewhat funny in this context. It is a very, very old ethnicity, but a very young nation. Under Denmark for 400 years, and united with Sweden for 110 years afterward, Norwegians have developed a unique sort of nationalism. I recently experienced my first Syttende mai—the 17th of May, Norway’s constitution day—in Norway. I was lucky to be invited to march in the parade alongside students and teachers from Oslo Katedralskole, the Cathedral School (among Oslo’s oldest schools, with a history that dates back to the year 1153). Afterward, I went to a barbecue with friends. Classic stuff. But on 17.mai, Norwegians dress up. All the way up. Those that have them wear a bunad, the traditional regional costumes developed the 1800s, associated with the cultural identities of each region. Those that don’t have a bunad simply put on their finest. There’s no question about it. I realized that on Seventeenth of May, Norwegians dress up, while on the Fourth of July, Americans dress down. Our national costume is jeans and a t-shirt. That’s not a bad thing, but it says something about the relationship we have (or don’t) with ethnicity, and with cultural history. Because of our relative national youth and our thoroughgoing multi-ethnicity, we don’t (and maybe shouldn’t) have a highly specific signal of our “belonging.” But with that comes the risk of not entirely knowing what, exactly, we belong to. That uncertainty can be productive; it ought to generate an openness to difference, to wildness, to the powers of improvisation and adaptation and care, but instead, because of the rotten core of our initial society, and the historical fallout that continues to shape the challenges we face, we’ve given a lot of space and energy to fear, foreclosure, and navel-gazing. That’s another thing that I’ve been struck by this year in Norway. There are problems, to be sure; there are plenty of Norwegians ([cough] Listhaug [cough]) here who are as cold, closed, and fearful as many Americans, when it comes to the question of belonging. There are also Norwegians who get a little smug about their belonging to Norway, who look down a bit at we backward Americans (without actually having been there, having met the millions of truly amazing people that call themselves “Americans”). But despite the strength of their ethnic identity, their traditionalism, their strong sense of Norwegianness, and the centuries-long luxury they’ve enjoyed of nurturing that identity in relative isolation, I’ve also seen and heard and experienced a remarkable willingness to share that sense of belonging with newcomers who have, at a cursory glance, very little natural “belonging” to the Norwegian society. Although it is imperfect, newcomers, immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers, are, to a surprising degree, welcomed, protected, and, with a little integration (that’s another essay with many parts), become contributors to something new, even in the outermost places, the farthest reaches, the isolated villages far above the Arctic Circle. In other words, despite its apparent cultural stasis, I’ve been surprised by Norwegians’ general willingness to let the very idea of “Norwegianness” change. We could learn a few things from Norway. But damn, it’s hard. And it’s gonna get harder. What a moment to live in. What a set of possibilities to inhabit.

So, here, at the border between this year-long magical world and that other magic of my usual life, I have a lot to think about, a lot to wonder over. I’m going to be fascinated—and surprised—by my memories for years to come, as they percolate up and take new shapes, push into new corners of my brain, new kroker i skogen (“nooks in the woods,” a little Norwegian phrase I like to think I coined). As I’ve mentioned before, my aloneness on these travels has given a special dimension to these travels. Those that know me know I’m a very social fellow; I thrive on togetherness. But it has been a powerful experience to rove throughout this fantastical landscape alone with my sea of thoughts. I felt, at times, a little like the young sailors in my favorite chapter of Moby-Dick, “The Masthead.” Alone, having clambered up to the crow’s-nest (and, aye, isn’t Norway, or, say, Svalbard, a sort of crow’s-nest on the ship o’ the world?!), that unsuspecting sailor experiences a sort of wonderful vertigo of self:

[L]ulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature; and every strange, half-seen, gliding, beautiful thing that eludes him; every dimly-discovered, uprising fin of some undiscernible form, seems to him the embodiment of those elusive thoughts that only people the soul by continually flitting through it. In this enchanted mood, thy spirit ebbs away to whence it came; becomes diffused through time and space; like . . . sprinkled . . . ashes, forming at last a part of every shore the round globe over.

There is no life in thee, now, except that rocking life imparted by a gently rolling ship; by her, borrowed from the sea; by the sea, from the inscrutable tides of God. But while this sleep, this dream is on ye, move your foot or hand an inch; slip your hold at all; and your identity comes back in horror.

Being alone here, with, on the other hand, a peculiar sort of familiarity with the country, having some drop of “viking blood” in my veins, after all, gave rise to thoughts and reflections in much the way that poor sailor seemed to glimpse all those elusive creatures of the deep and begin to diffuse his own identity amongst theirs, unknowable as they really were. That wildness of encounter. In my own diffusion, I fell most in love with Nord-Norge, Northern Norway. I’d always, as I’ve said, been drawn to the northernmosts, and I managed to spend over fifty days “near the bear.” I recently discovered that the word Arctic comes from the Greek arktos, meaning “the bear,” and arktikos, or “of the bear,” referring, of course, to the constellation, the Great Bear, which, to Greek eyes, stands in the northern skies. Thus, to be in the Arctic is to be “near the bear.” A pretty thought, that. And up there, one can easily take the nordlys for another image of those thoughts that continually flit through the mind, lending it an equally fleeting sense of identity, a place.

And so, as ever, images:

The view westward from Keiservarden on my last visit to Bodø. Landegode to the right and Lofoten in the distance beyond.

The iconic split peak of Kinnaklova on Øya Kinn, the Island of Kinn, Sogn og Fjordane. (The excellent Kinn Brewery takes its name from the island and its logo from Kinnaklova.)

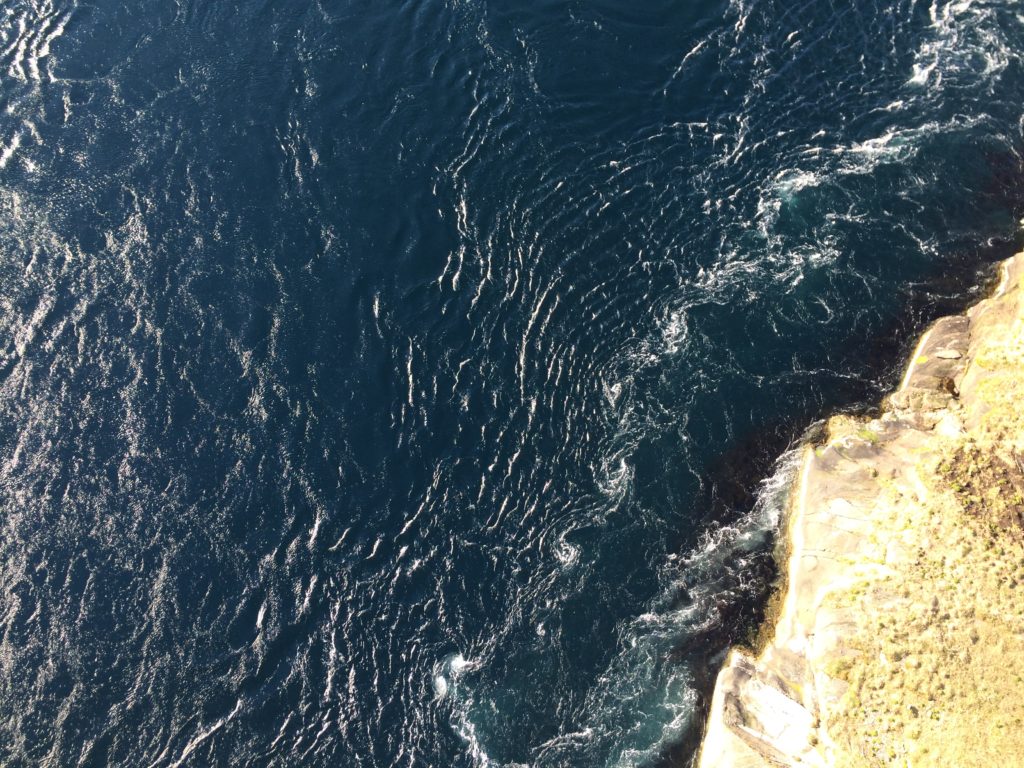

Looking westward from the top of Søre Stauren, the southern peak of Kinnaklova (the point at center is the pointed peak to the right in the images above). Furet, værbitt over vannet.

1Sharp-eyed (or norskspråkelige) readers will notice the variant spelling: vidare for videre, gåande for gående, and skule for skole. That’s nynorsk, New Norwegian, Norway’s other official language. Flora was the only VGS and Sogn og Fjordane the only fylke I visited that uses nynorsk for all its official goings-on.